The dreaded and ballyhooed recession remains at bay for the moment. In fact, much of the recent news concerning the economy has been great. GDP growth at the end of last year was remarkably strong. Jobs creation is still super-charged. Unemployment rates are holding fast at minimal levels. Retail sales have been booming. ɫ��ɫ’s own ‘starts’ statistics, supported by ‘mega projects’, began 2023 with a bang. And inflation is continuing to abate.

That last point is especially important. Current recessionary fears stem mainly from the financial side of business and personal affairs. Climbing interest rates make it harder to pay for loans and inhibit all manner of borrowing. Pricier mortgage rates tamp down new and resale home buying. Plus, banks inevitably become more careful with their lending. Capital spending on medium and smaller-sized construction projects is often a casualty.

That last point is especially important. Current recessionary fears stem mainly from the financial side of business and personal affairs. Climbing interest rates make it harder to pay for loans and inhibit all manner of borrowing. Pricier mortgage rates tamp down new and resale home buying. Plus, banks inevitably become more careful with their lending. Capital spending on medium and smaller-sized construction projects is often a casualty.

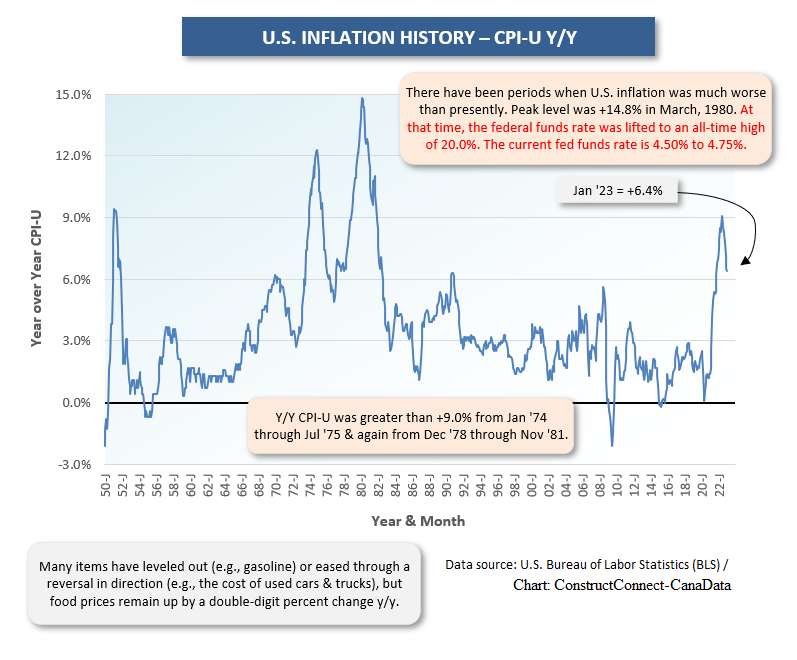

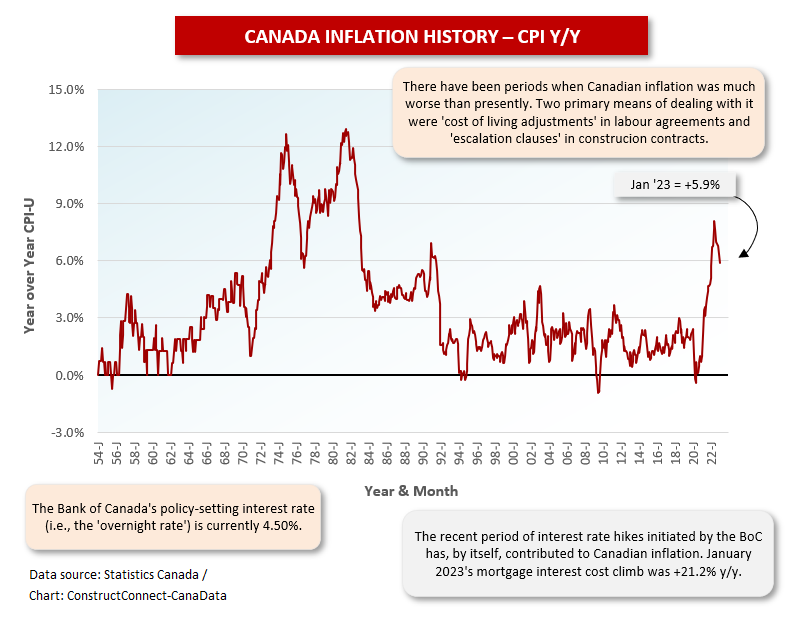

The fact that interest rates are up, although not nearly as dramatically as one might suppose ��̶ ��i.e., see Graphs 7 and 8 for historical context�� ̶�� rests squarely with inflation. The Federal Reserve and the Bank of Canada and other central banks around the globe have been lifting rates to try to rein in prices (which is also to say, costs).

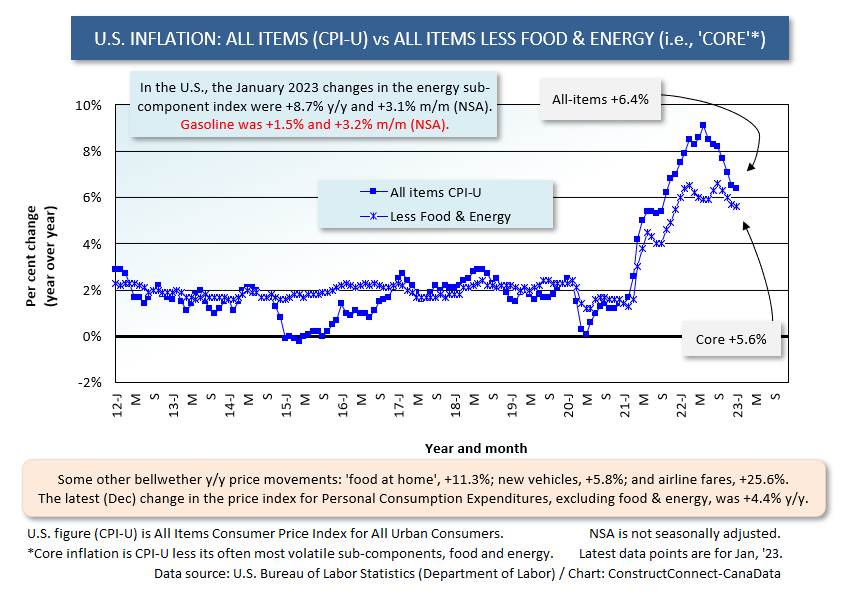

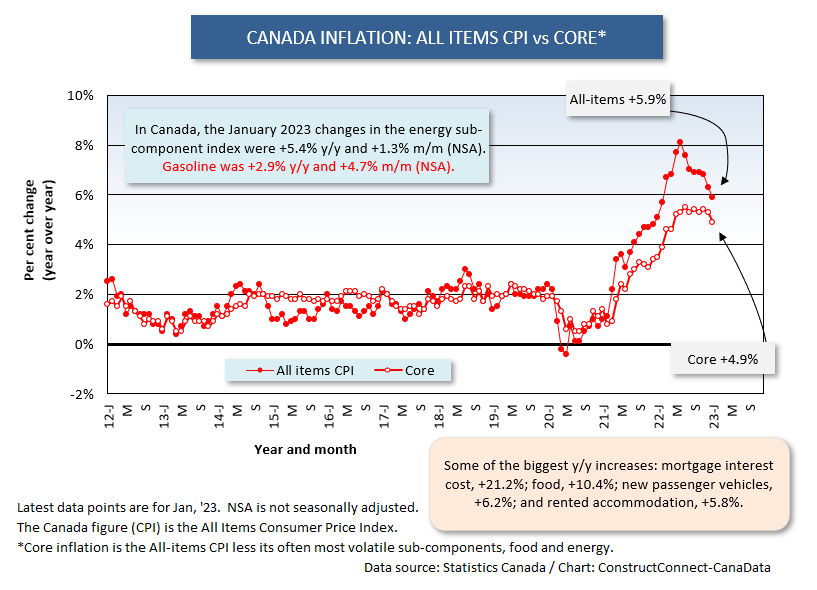

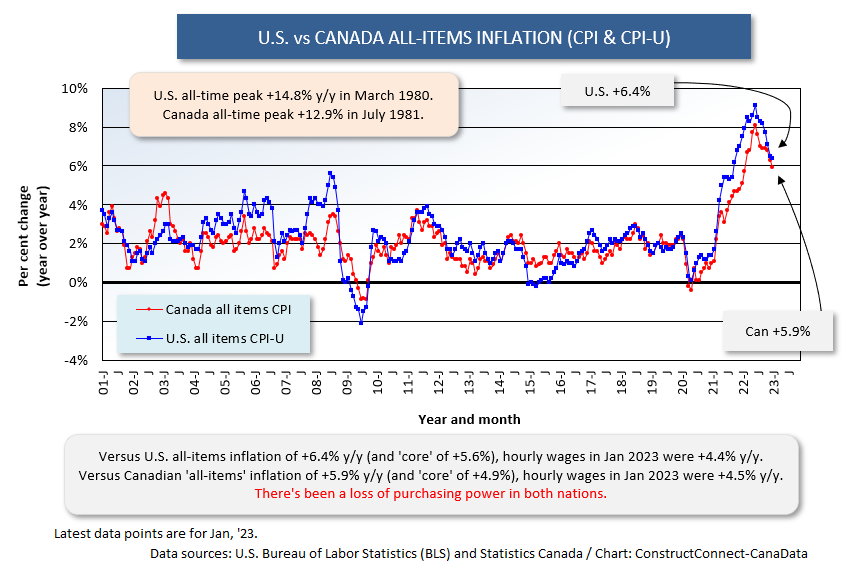

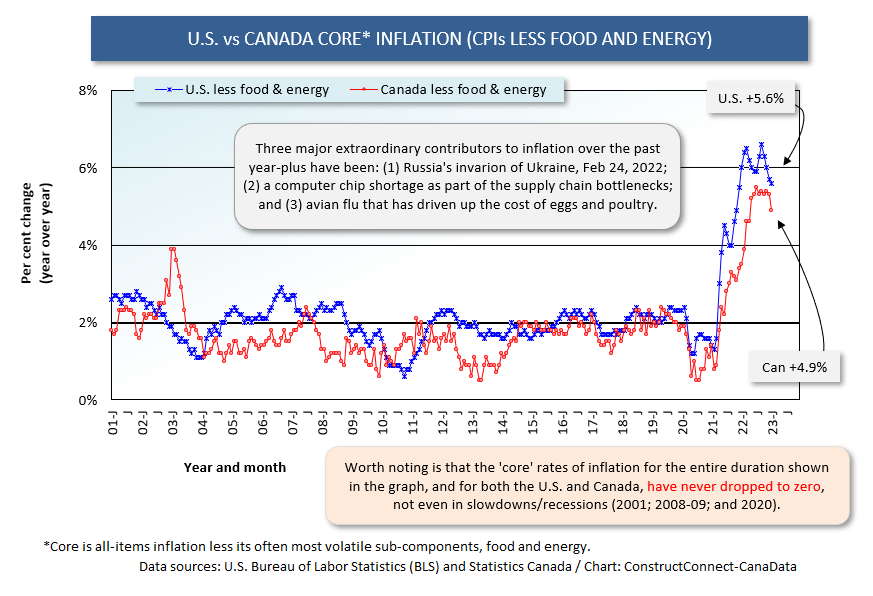

The Fed and the Bank of Canada, themselves, have been questioning whether they still need to apply the squeeze. Graphs 1 and 2 demonstrate that inflation has been moderating in both countries. The cost of gasoline, in particular, has flattened on a year-over-year basis. When the cost of filling up at the pump settles, it’s a mood changer that leans towards optimism.

Most of the stress on prices is now coming from food sub-indices in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), where there continue to be double-digit percentage changes. Two of the key drivers of inflation, discussed in the text box accompanying Graph 4, have had outsized impacts on the price of baked goods and meat: (1) Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (suppressing wheat exports) a year ago on February 24, 2022; and (2) an outbreak of avian flu internationally, reducing the supply of eggs and poultry products.

But there’s also wobbly logic arising from the inflation fight that certainly warrants attention. Statistics Canada, to its credit, has been quite forward in shining a light on this phenomenon.

Among the CPI line items that are now contributing the biggest year-over-year jumps is ‘mortgage interest cost.’ In January, it was +21.2% y/y.

The intended cure, higher interest rates, is directly worsening the problem that’s meant to be fixed, inflation that is out of hand.

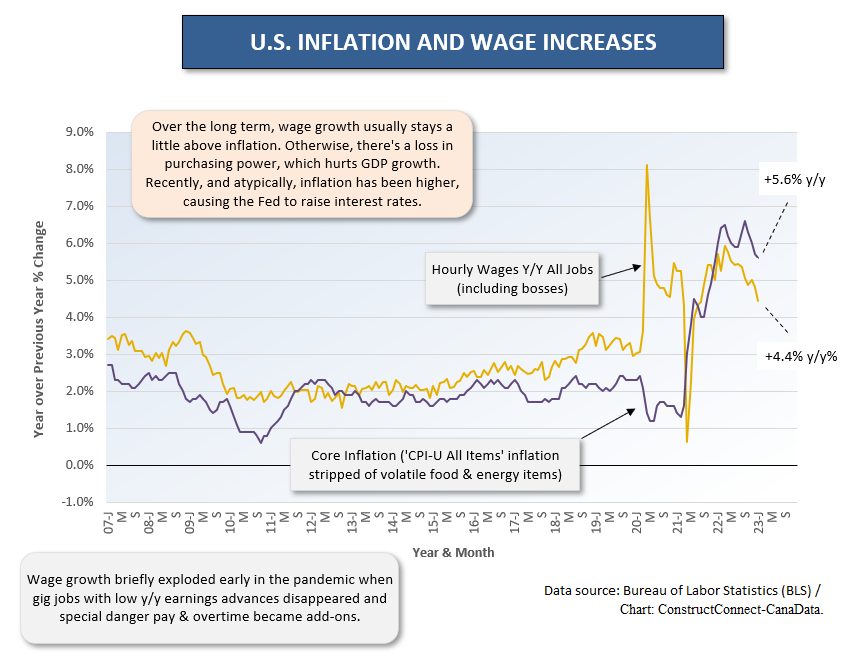

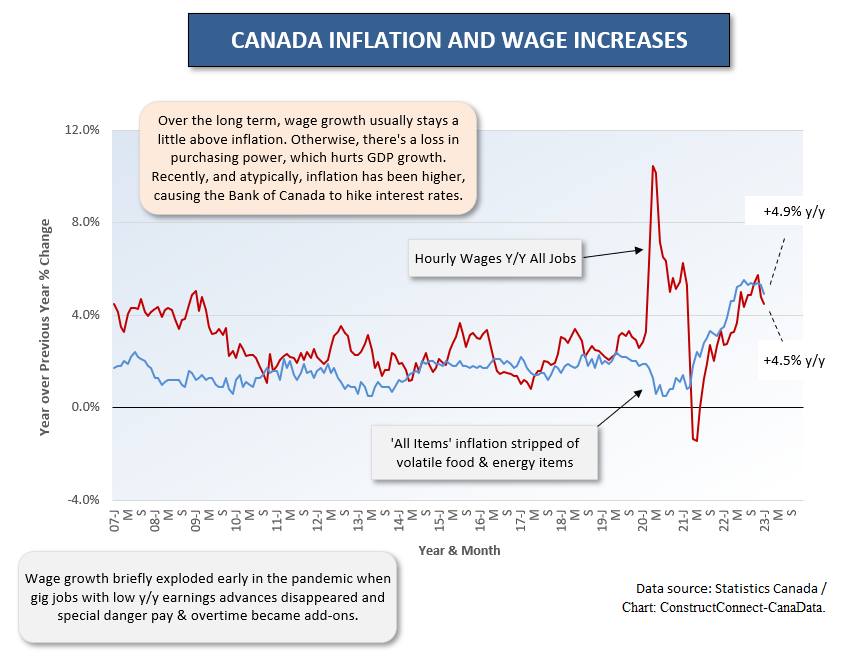

Finally, a key issue with inflation is the degree to which it takes away purchasing power. History holds that, for workers to be happy, their earnings should increase faster than inflation. This is the formula for achieving a better standard of living. Over time, you can buy more ‘real’ goods and services.

In Graphs 5 and 6, year-over-year wages do outperform inflation in most of the years shown. Lately, though, it’s been price change exceeding compensation change. That is definitely not a desirable situation. This is another major reason central bankers have been on a rate-tightening binge. ��

But in terms of whether the moment has arrived to pack away the interest rate weaponry, a nod in that direction comes from the observation that both inflation and wage increases have, most recently, exhibited slippage to the downside.

Graph 1

Graph 2

Graph 3

Graph 4

Graph 5

Graph 6

Graph 7

Graph 8

Alex Carrick is Chief Economist for ɫ��ɫ. He has delivered presentations throughout North America on the U.S., Canadian and world construction outlooks. Mr. Carrick has been with the company since 1985. Links to his numerous articles are featured on Twitter��, which has 50,000 followers.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed