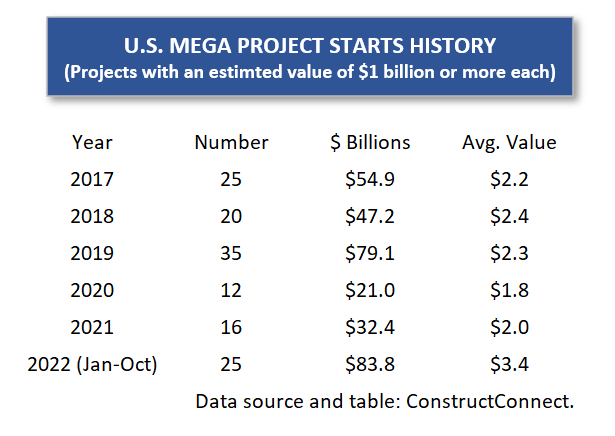

The current year, 2022, is shaping up to be the best ever for mega project initiations. ‘Megas’ are projects carrying an estimated construction value of a billion dollars or more each. For many of these projects, there’s also a machinery and equipment component in the total capital spending or investment figure that is often roughly equivalent to the construction cost.

In ɫ��ɫ’s ‘starts’ statistics, through October of this year, there are 25 mega project starts for a combined dollar value of $83.8 billion. 2019 was the previous best period, when there were 35 megas through the full year, adding to $79.1 billion.

In ɫ��ɫ’s ‘starts’ statistics, through October of this year, there are 25 mega project starts for a combined dollar value of $83.8 billion. 2019 was the previous best period, when there were 35 megas through the full year, adding to $79.1 billion.

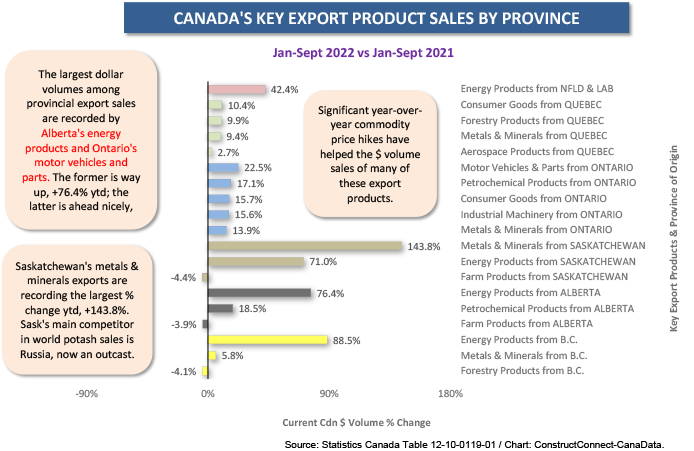

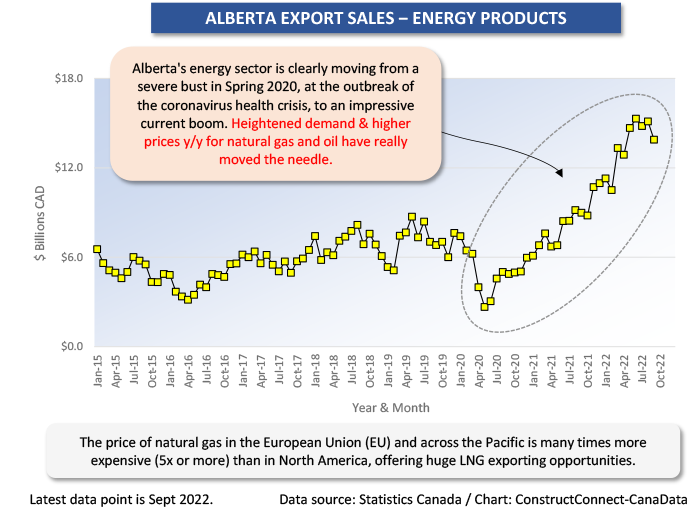

A key factor inspiring owners to proceed with many of the nation’s largest construction projects is the opportunity for export sales. This is particularly true in the sphere of natural resources. To go a step further, while those opportunities exist in some other areas, such as agriculture (with the building of immense soybean processing plants, as just one example), they have especially come to the fore in the field of energy products.

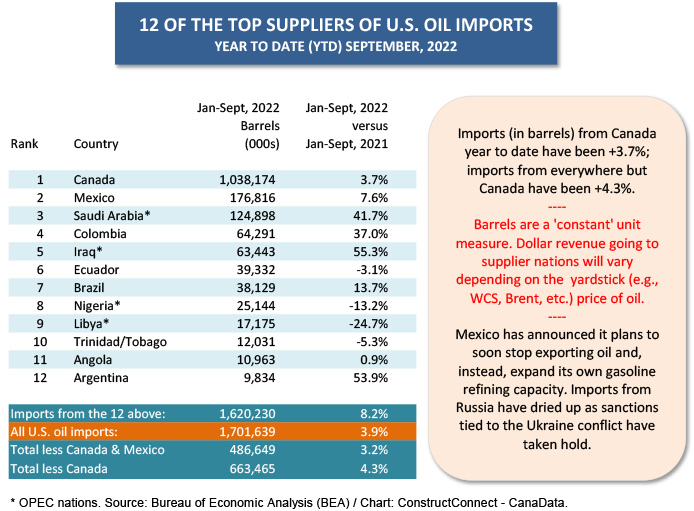

Due to hydraulic fracturing, the U.S. is no longer as dependent on the rest of the world for oil and natural gas as it once way. In fact, the U.S. is back in the game of exporting energy products.

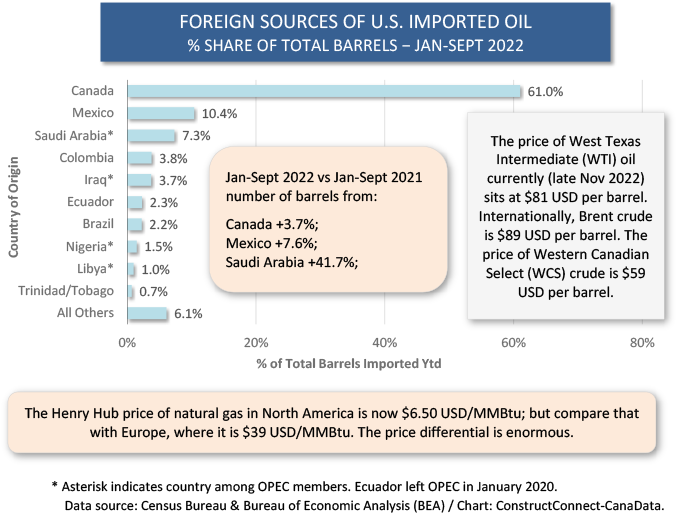

Deprived of Russian energy supplies, as a fallout of the Ukraine conflict, Europe is desperate for oil and gas from alternative suppliers. A huge differential in price has opened between natural gas extracted in North America, at around $6 USD per mcf (or MMBtu), and deliveries made to Europe, or Asia for that matter, beginning at $30 USD/mcf and going skyward from there.

Within the U.S.-Canada economic zone, oil and natural gas are moved by pipeline or rail car. Those aren’t options for shipments to overseas markets. The most convenient way to move gas across the vastness of oceans is in liquefied form. But that means spending billions of dollars on liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporting facilities. Turns out, it’s now worth it.

LNG terminals are already up and operating in several U.S. coastal states. And there’s plenty more such work planned for the likes of Texas and Louisiana.

Nor will the foreign-trade-driven major energy projects of the future be limited to oil and LNG deep-water exporting sites. Hydrogen and ammonia are two chemicals requiring major capital expenditures for extraction from fossil fuels or production by other means, such as electrolysis. This is under the supposition that they will play important roles in the transformation of the world economy to net zero carbon emissions by mid-century.

By the way, ‘blue’ hydrogen derived from fossil fuels is not considered a ‘clean’ source; ‘green’ hydrogen from electrolysis, though, is viewed by environmental monitors as ‘friendly’, provided the electricity used along the way is from renewable sources (e.g., hydro, wind, solar, geothermal).

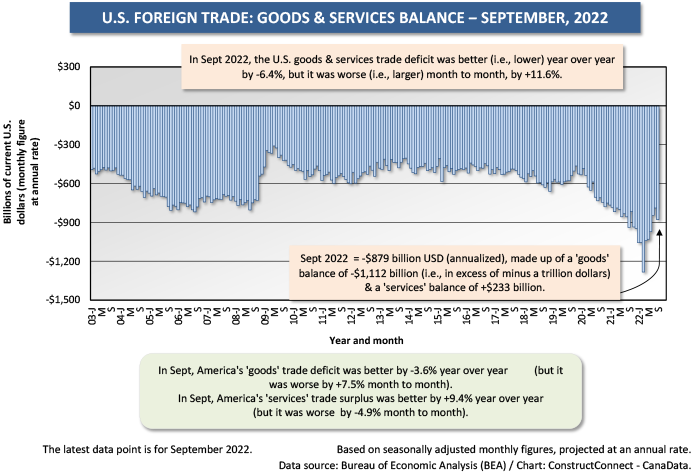

Because of the changes occurring in the global energy marketplace, the U.S. foreign trade deficit is shifting from a deeply negative position to one that’s not quite as alarming (Graph 2).

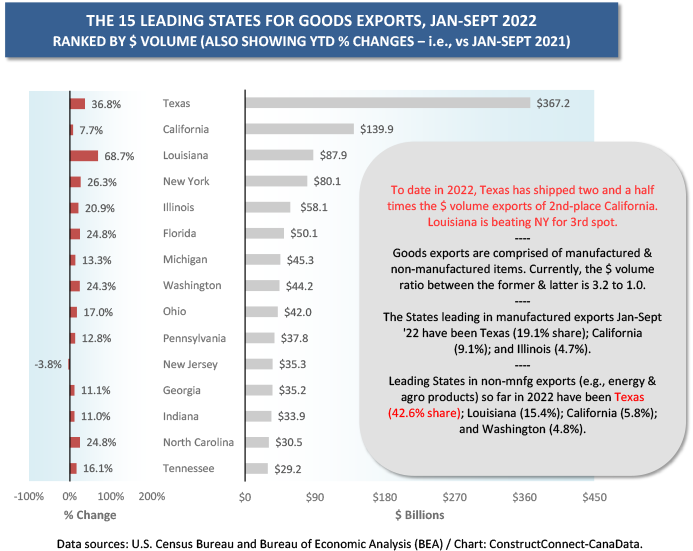

Texas is America’s Export Sales Leader

Among states, Texas as an energy giant is by far America’s export sales leader (Graph 4). Through the first three quarters of this year, the dollar volume of exports leaving Texas has been two-and-a-half times greater than what has been shipped from the state in second spot, California.

In third place for export sales is another Gulf-facing state, Louisiana. LA, which has impressive prospects for the building of more huge energy-exporting facilities (mainly LNG-based) beyond those that are already in place, is beating fourth-place New York for foreign shipments.

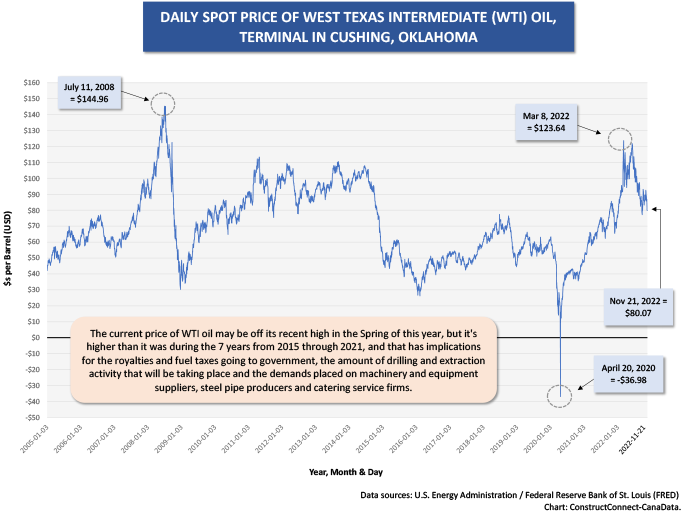

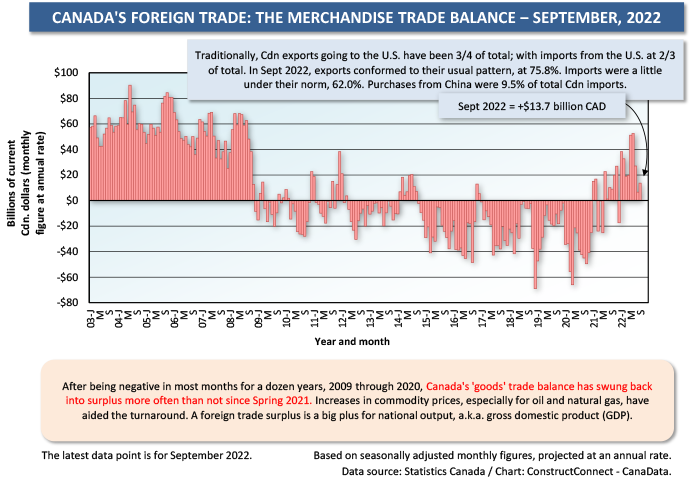

There’s a similar picture for Canada. Graph 7 shows the big swing in Canada’s merchandise trade position, from monthly deficits to surpluses, over the past year plus. The international price of oil may have retreated from its recent peak in the spring of this year, but it’s still way up compared with the seven years from 2015 to 2021 (Graph 1).

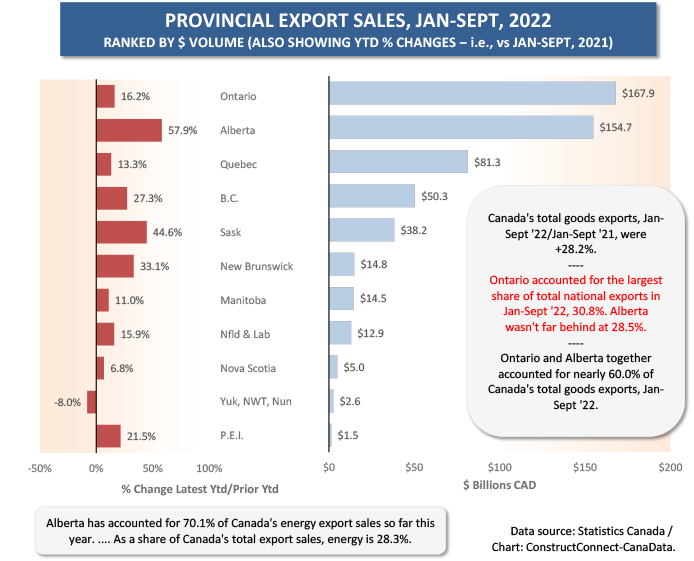

As a result, the energy-rich provincial economy of Alberta is enjoying a full-blown revival. Alberta, with less than a third of the population, is only a little behind first-place Ontario in year-over-year jobs creation. The same goes for export sales (see Graph 7). Ontario and Alberta are running neck and neck at the front of the provincial pack for dollar volume of export shipments.

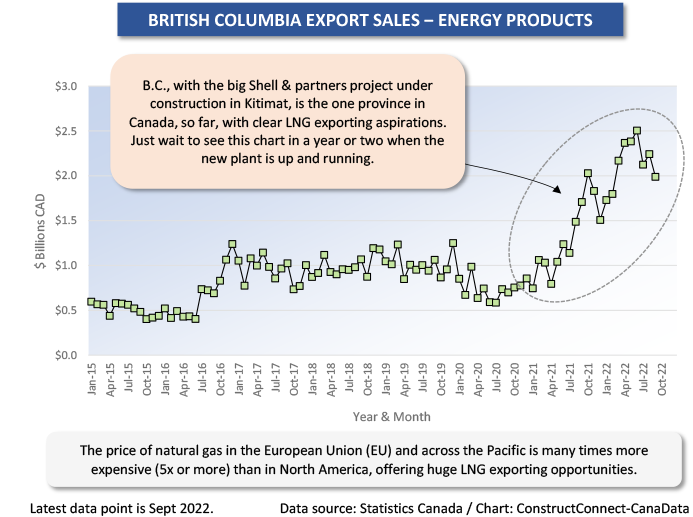

Graph 9 shows the takeoff in Alberta exports of energy products. Graph 10 is just as striking, but it’s for British Columbia’s energy export sales, which are weighted towards natural gas and hydroelectricity.

Furthermore, B.C. has a special reason to crow at this time. It has been the only province in the country, so far, to embrace the possibilities presented by the Pacific Region’s thirst for LNG. The Canada LNG project, backed by Shell and a group of international partners, is being built in Kitimat, with a gas supply pipeline running to it from the northeast corner of the province.

When Canada LNG comes onstream in a year or two, it will propel B.C. into a far more prominent role among the provinces as an energy powerhouse. There are more such projects on the drawing boards.

LNG Import Terminals in Germany

As a final note, there’s encouraging news concerning the ability of energy-strapped LNG importers to accept incoming product. Germany is fast tracking construction of terminals at which modified super-tankers will be able to dock and covert cooled LNG back into gaseous form as its being offloaded. The first of five such facilities has just been completed in Wilhelmshaven at the edge of the North Sea, west of Hamburg.

The Wilhelmshaven terminal has been built in record-short time, less than 200 days, under emergency measures that expedited approvals processes and largely ignored environmental concerns. The latter became a casualty when weighed against the prospect of the citizenry shivering by candlelight in winter. Through this means, Germany is hoping to replace about half of the cut-off natural gas that was previously arriving in the country by pipeline from Russia.

Table 1

Graph 1

Graph 2

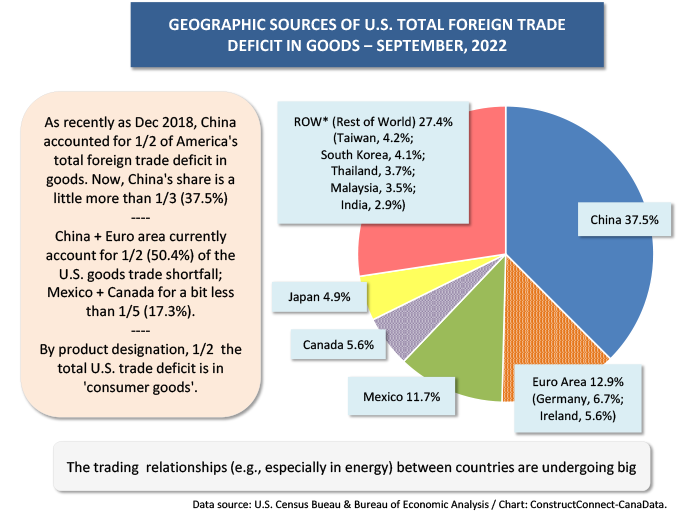

Graph 3

Graph 4

Table 2

Graph 5

Graph 6

Graph 7

Graph 8

Graph 9

Graph 10

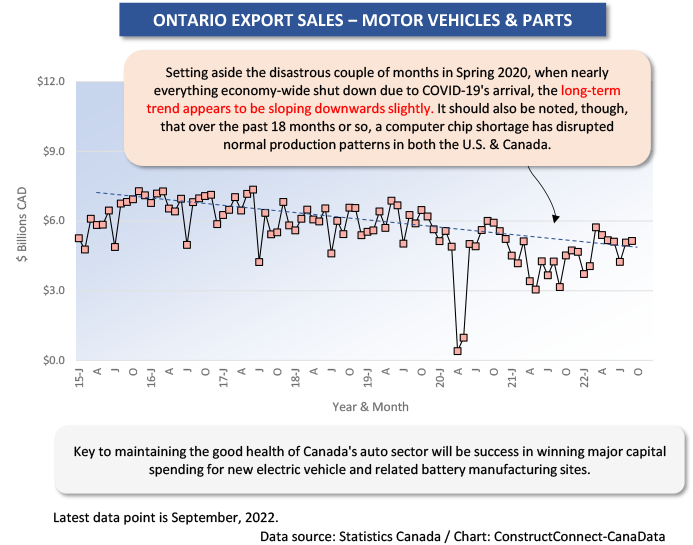

Graph 11

Alex Carrick is Chief Economist for ɫ��ɫ. He has delivered presentations throughout North America on the U.S., Canadian and world construction outlooks. Mr. Carrick has been with the company since 1985. Links to his numerous articles are featured on Twitter , which has 50,000 followers.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed