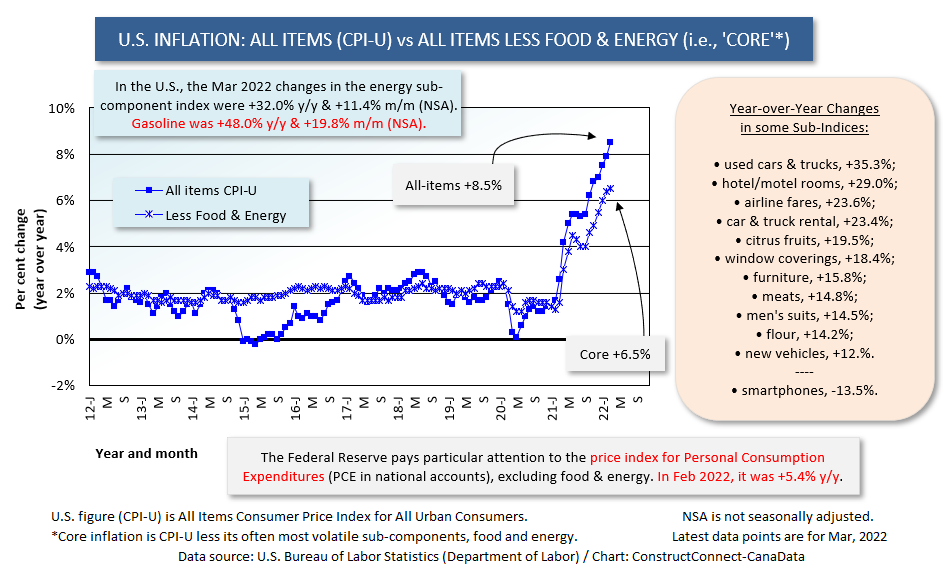

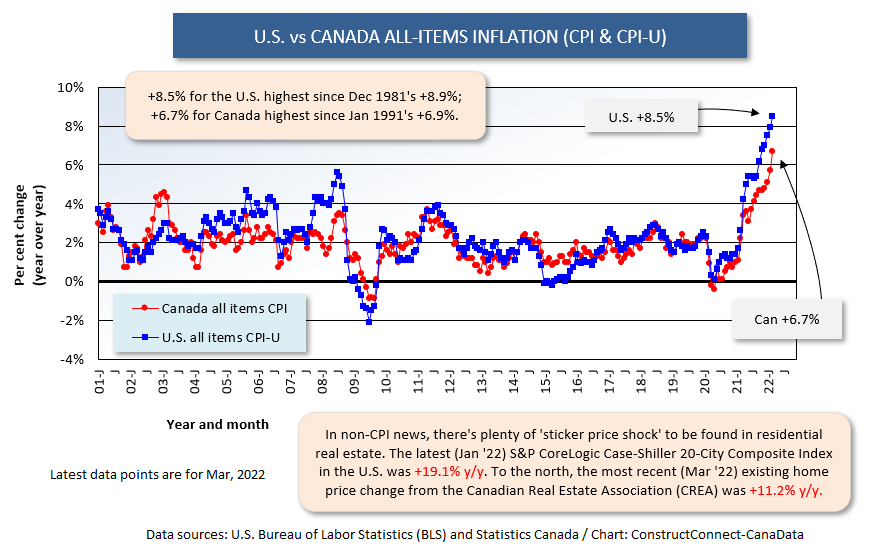

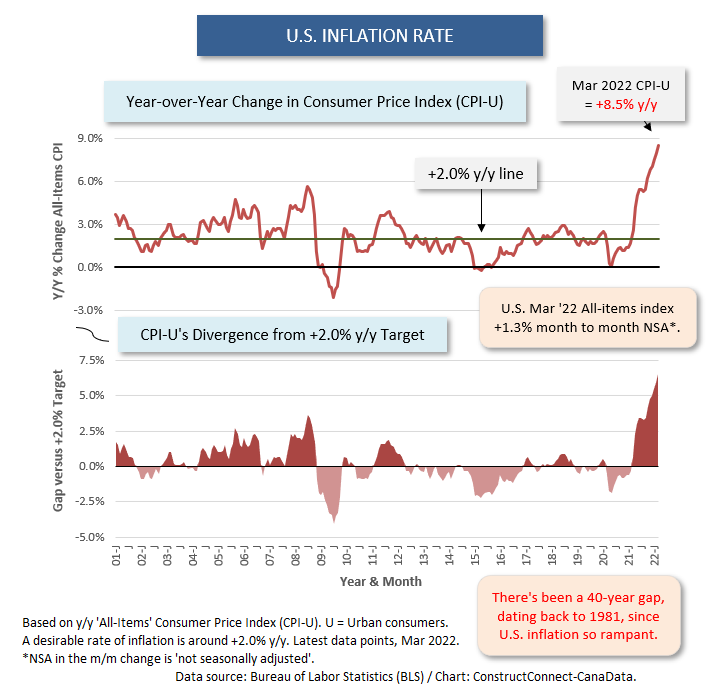

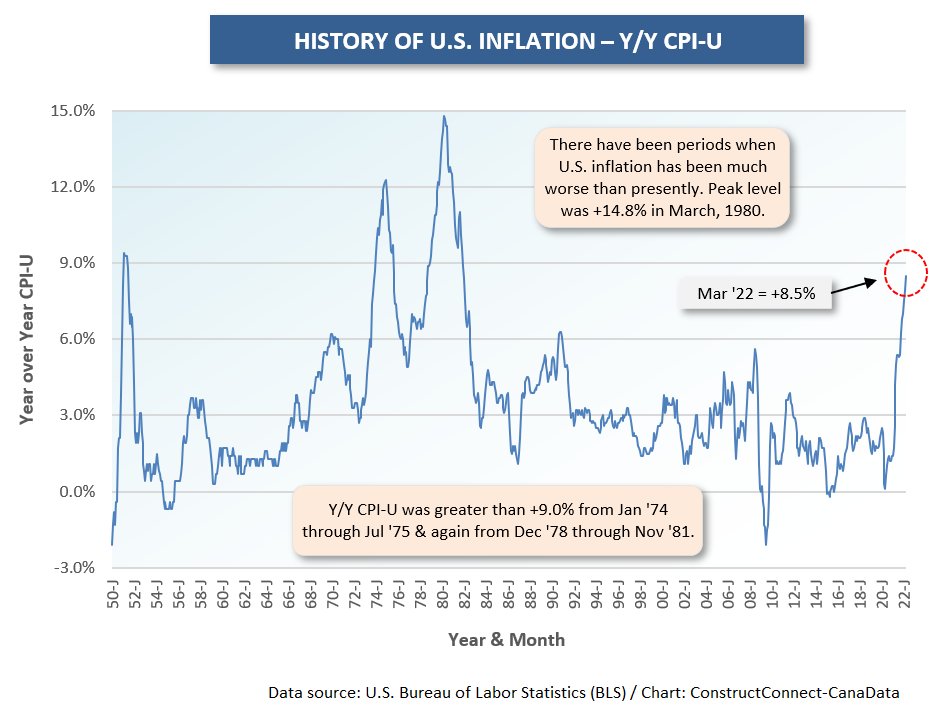

U.S. current (March) inflation of +8.5% year over year for the All-items Consumer Price Index (i.e., known as CPI-U, with the ‘U’ signifying that it’s for urban consumers) is the highest this century. It’s more than four times greater than the +2.0% figure usually accepted as the desirable target. A little inflation is judged to be a good thing for the economy. Through making it easier to pay off loans, it greases the wheels of industry.

What +8.5% is not, though, is unique in a historical context. From 1951 through 1981, there were 59 months, or the equivalent of nearly five years, in which CPI-U exceeded +9.0% y/y. The most notable periods of extreme inflation occurred from January 1974 through July 1975 and from December 1978 through November 1982. Peak inflation was +14.8% y/y, recorded in March 1980.

What +8.5% is not, though, is unique in a historical context. From 1951 through 1981, there were 59 months, or the equivalent of nearly five years, in which CPI-U exceeded +9.0% y/y. The most notable periods of extreme inflation occurred from January 1974 through July 1975 and from December 1978 through November 1982. Peak inflation was +14.8% y/y, recorded in March 1980.

There’s a great tradition among economists of arguing over what causes inflation. The discourse has pitted money supply theorists against those who keep a wary eye on excessive fiscal deficits. Plus, there’s the cost-push versus demand-pull impact to be sorted out.

Due to the extraordinary measures adopted by nations around the world to deal with the coronavirus pandemic, all of these have come into play in explaining our current dilemma. Employing snappier wording, this latest bout of inflation ‘has it all’.

Not so long ago, central banks engaged in quantitative easing and lowered ‘real’ interest rate to zero and less. Governments opened the spigot on spending to provide income support for laid-off workers and for the myriad companies facing bankruptcy.

We’re now faced with the consequences.

A key offshoot of excessive inflation is higher interest rates, initiated by central banks to rein in borrowing and spending. There’ll be less of the demand-pull scenario where too much money is chasing too few goods.

On the supply side, the subject of logistical bottlenecks leading to production (think computer chips) and material shortages has dominated the headlines for a year. Adding extra fuel to the cost-push fire is the fighting in Ukraine that is interrupting international trade flows in energy and agricultural products.

All of this leads to the subject of workarounds. None of us needs to be entirely passive in our victimhood.

At a time when the price of petrol is soaring, we can take public transit as opposed to filling up our gas guzzlers. This is one example of how the current times are fortuitous in that so many of us are still working from our homes.

We can switch brands of cereal, jams, cleaning supplies, clothing lines, etc. We can mix up our choice of meats or opt for more vegetables in our diets. I’d suggest eating more pasta, but that may become problematic with Ukrainian exports of wheat tailing off.

There’s a good reason ‘dollar’ stores and other discount outlets are thriving.

Purchases of big-ticket items (appliances, furniture) can be postponed. ��

But here’s the rub, of course. Delaying those purchases will have a deleterious impact on GDP growth. This has already become apparent. 2022’s Q1 GDP growth estimate from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) has just been released and it’s a disappointing -1.4% annualized.

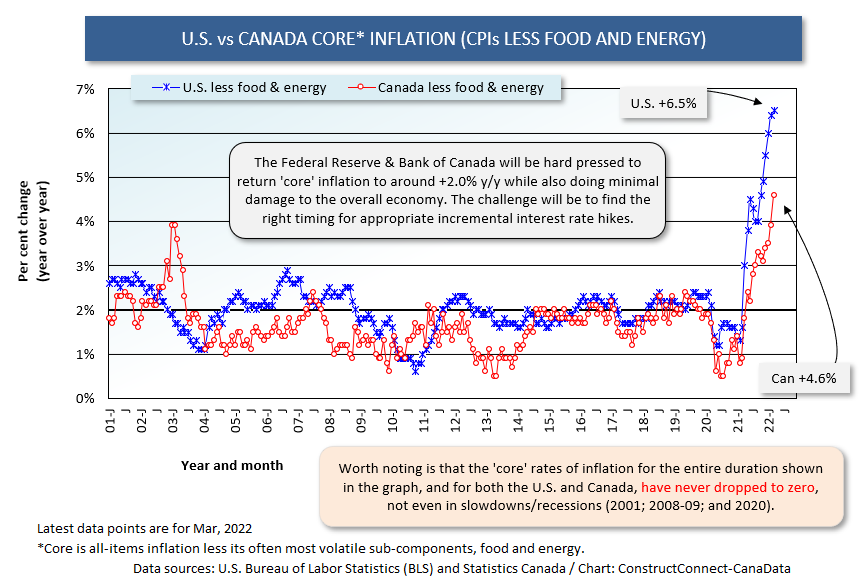

Graph 1

��

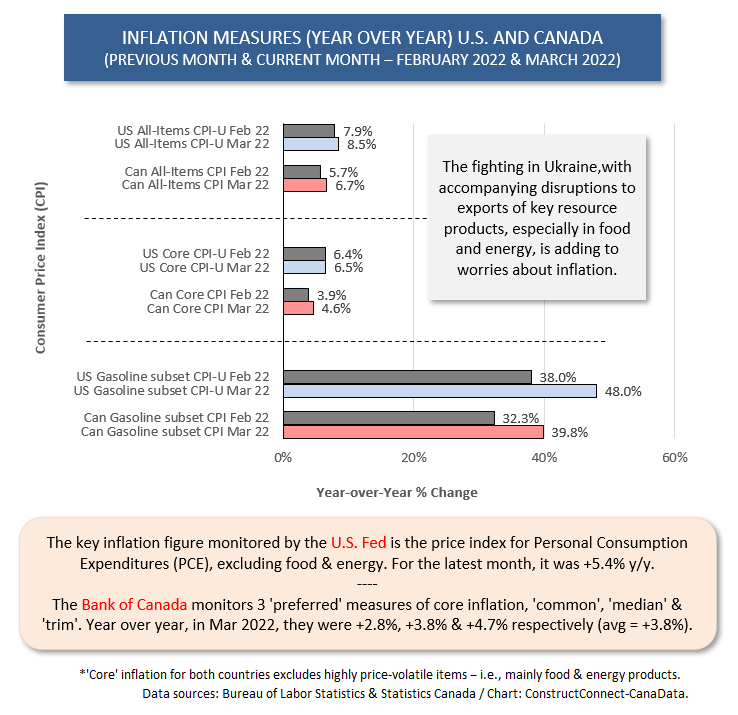

Graph 2

Graph 3

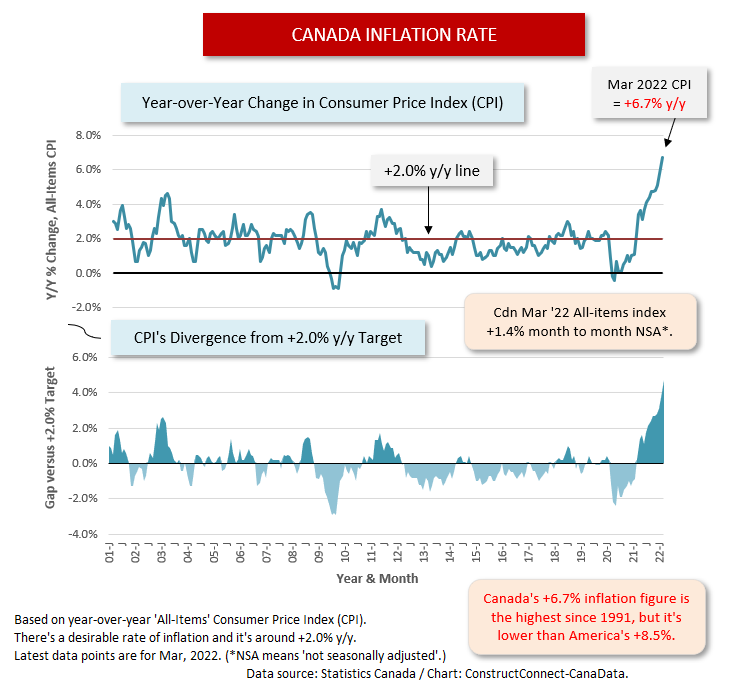

Graph 4

Graph 5

Graph 6

Graph 7

Graph 8

Alex Carrick is Chief Economist for ɫ��ɫ. He has delivered presentations throughout North America on the U.S., Canadian and world construction outlooks. Mr. Carrick has been with the company since 1985. Links to his numerous articles are featured on Twitter��, which has 50,000 followers.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed